| Author | Post |

|---|

Chad_Engbers

Member

| Joined: | Tue Jul 5th, 2011 |

| Location: | Michigan USA |

| Posts: | 7 |

| Status: |

Offline

|

|

Posted: Tue Jul 5th, 2011 06:03 pm |

|

Especially before Paracelsus, alchemists widely understood the opus as the uniting of an active male principle or essence--sulphur--with a passive female one--mercury. (Other binaries might be invoked here, as well).

It seems to me that a similar relationship exists between the alchemist himself and nature in the process of the work: the alchemist is actively manipulating elements, often with heat, but he must also allow the more passive laws of nature to run their course without his intervention.

Prefaces to alchemical works often caution against an imbalance of art over nature: the alchemist cannot make anything he wants, nor can he perform the work as quickly as he wants. Anyone who claims otherwise is a charlatan. There needs to be a cooperation, a union, between the adept's activity and those natural processes that would go on with or without him.

What I am suggesting is a syncdoche of the microcosm/macrocosm variety, but on a smaller scale: the union of opposites in the alembic is also happening between the alchemist and nature.

My questions are two:

1) Does this analogy seem accurate?

2) Is anyone familiar with places in alchemical literature where the alchemists themselves mention such an analogy--e.g., identifying the artificial work of the adept with the sulphiric principle?

Thanks,

ChadLast edited on Tue Jul 5th, 2011 06:04 pm by Chad_Engbers

|

adammclean

Member

| Joined: | Fri Sep 14th, 2007 |

| Location: | United Kingdom |

| Posts: | 606 |

| Status: |

Offline

|

|

Posted: Wed Jul 6th, 2011 11:23 pm |

|

The Sulphur-Mercury theory of the growth of metals in the earth appeared early in the history of alchemy. Thus the original idea was based on physical substances supposedly found in the earth, in the root of mines.

There is a good article online

http://www.history-science-technology.com/Summa/summa7.htm

Later alchemists, evolved this idea further and turned these into "principles" found in all matter and aspects of creation. By the Seventeenth Century, many alchemical authors had begun exploring a spiritual side of alchemy, and from that time on Sulphur and Mercury were used in a multiplicity of contexts.

As to parallels between the union of opposites in the alembic and what is happening between the alchemist and nature, this is a key part of the Jungian narrative of alchemy. I am not sure it is necessarily so easily found in that precise form within alchemist's writings.

Jung is mischievous in his manipulation of ideas. I have already pointed out on another thread Jung use of the Hexastichon images. In his Psychology and Alchemy on page 415 (of my copy) he describes an image from the Hexastichon as "Coniunctio as a fantastic monstrosity" with a further mention of this in the text below as "The brother-sister pair stands for the unconscious..." This is complete rubbish. If one reads the description of the label "8" marking the man and woman in the facing page of the Hexastichon, one sees this is described as the "Woman taken in adultery" (De muliere deprehensa in adulterio). This image is, in fact, part of a memory system for remembering key parts of the four Gospels, this one being for the Gospel of John.

Perhaps we might say that Jung was just reading something into an unfamiliar image and did not know its context. Not really, as he had this very book in his personal collection. He could easily see the label. That is why I so mistrust Jung's approach. He thought he could get away with mere rhetoric and that few people would know enough about this obscure material to be able to see through his interpretations and challenge them. Jung cannot be trusted. One has to deconstruct every statement he makes.

Sadly, people believe in Jung's ideas, with all the intensity of a religion. I often wish some scholar would just take one of his books on alchemy and show all the distortions and false interpretation he lays onto alchemical text and visual material, so we can move on from "Jungian alchemy".

To understand alchemy one must go back to the original writings of the alchemists, their books and manuscripts.

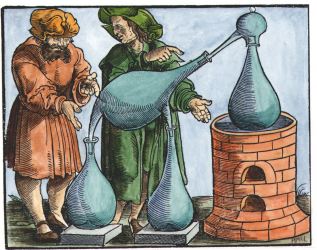

To trawl through texts looking to confirm the ideas of a mid-twentieth century manipulator seems unlikely to uncover much truth.Attached Image (viewed 1678 times):

|

Chad_Engbers

Member

| Joined: | Tue Jul 5th, 2011 |

| Location: | Michigan USA |

| Posts: | 7 |

| Status: |

Offline

|

|

Posted: Thu Jul 7th, 2011 01:13 pm |

|

Thanks, Adam; that response is very helpful.

I agree that Jung plays a little fast and loose with alchemy--and with other things. (See the way he introduces the case study in part two of Psychology and Alchemy. He's trying to maintain scientific objectivity by not interacting with the analysand himself, but he proceeds to impose on the young man's dreams all sorts of images yanked from all sorts of contexts, and he has even edited the dreams themselves down to what he--Jung--considers their most important components! So much for objectivity, right?)

The parallel that I'm suggesting here is a little bit different from Jung's claim that the alchemists are working out projections of their own unconscious minds in their work and writings. That claim of Jung's pyschologizes alchemy by reducing it to dynamics of the psyche: what seem to be external elements and processes are really, in some sense, all in the head of the alchemist.

I'm suggesting that the work requires the adept to unite with forces -outside- his head. Jung would interpret sulphur and mercury as conscious and unconscious, respectively (the two halves of the alchemist's psyche); I'm suggesting that they might be interpreted as alchemist and Nature-beyond-the-alchemist.

To your point that this connection does not often appear in the writings of the alchemists themselves, I can only register some slight surprise, because those writings are filled with admonitions to curb the alchemist's own active ambitions, to moderate the heat used in the process, etc.

It seems such a small step to associate those warnings with sulphrous properties in the alchemist himself, and alchemical writings--especially the later ones--often make much larger steps in extrapolating between physical and spiritual phenomena, etc.

But I of course defer to the knowledge of scholars who have read far more in this field than I, and as I say, I'm quite grateful for the feedback.

|

adammclean

Member

| Joined: | Fri Sep 14th, 2007 |

| Location: | United Kingdom |

| Posts: | 606 |

| Status: |

Offline

|

|

Posted: Thu Jul 7th, 2011 01:56 pm |

|

Chad_Engbers wrote:

Jung would interpret sulphur and mercury as conscious and unconscious, respectively (the two halves of the alchemist's psyche); I'm suggesting that they might be interpreted as alchemist and Nature-beyond-the-alchemist.

As I indicated the original conception of the Sulphur-Mercury theory became extended by later alchemists, and by the 17th century you can find a multiplicity of ideas about this. Here are just a few examples of reworking this idea - the texts can be found on the Alchemy Web Site.

Edward Kelly de Lapide Philosophorum

Jean de Meung - The Remonstrance of Nature

Philalethes - Brief Guide to the Celestial Ruby

Alchemical writings do not cohere over hundreds of years. There is no one sustained view of alchemy among alchemical writers. Indeed, there is a kind of tension between an original idea and a creative reworking of that. This leads to some alchemists extending an idea into new domain, then others responding to this by trying to return to the original concept.

So I feel sure your idea of alchemist and Nature-beyond-the-alchemist, will be found in some form amongst the mass of alchemical writings. Alchemists lived in a world which accepted a Christian narrative, so they understood the term "spiritual" within that context, rather than the idea of "spiritual" which holds today (which can be divorced from a religion as such). The obvious example of a writer developing a spiritual alchemy would be Jacob Boehme. This became very influential on some later writers. Perhaps in his work you might find something that resonates with your thesis.

|

Chad_Engbers

Member

| Joined: | Tue Jul 5th, 2011 |

| Location: | Michigan USA |

| Posts: | 7 |

| Status: |

Offline

|

|

Posted: Thu Jul 7th, 2011 10:57 pm |

|

| All of these leads are exactly what I needed. Thanks again, Adam.

|

Current time is 09:38 am | |

|

|

|