|

|

Based on the book Introduction to the History of Scienceby George Sarton (provided with photos and portraits) Edited and prepared by Prof. Hamed A. Ead These pages are edited by Prof. Hamed Abdel-reheem Ead, Professor of Chemistry at the Faculty of Science -University of Cairo, Giza, Egypt and director of the Science Heritage Center E-mail: profhamedead@yahoo.com Web site: http://www.frcu.eun.eg/www/universities/html/shc/index.htm Back to Islamic Alchemy . Back to reference library . The ninth century was essentially a Muslim century. To be sure, intellectual work did not cease in other centuries; but the activity of the Muslim scholars and men of science was overwhelmingly superior. They were the real standard-bearers of civilization in those days. Their activity was superior in almost every respect. To consider only the first half of the century, the leading men of science, al-Kindi, the sons of Musa, Al-Khwarzmi, al-Farghani, were all Muslims; Ibn Masawaih, it is true, was a christian, but he wrote in Arabic. Cultural Background The seventh Abbasid caliph, al-Ma'mun (813-833), was even a greater patron of letters and science than Harun al-Rashid. He founded a scientific academy in Bagdad, tried to collect as many Greek manuscripts as possible, and ordered their translation; he encouraged scholars from all kinds, and an enormous amount of scientific work was done under his patronage. al-Ma'mun

An Encyclopedic Scientist.... Al-Kindi Abu Ysuf Ya'qub ibn Ishaq ibn al-Sabbah al-Kindi

(i. e., of the tribe of Kinda) Latin name, Alkindus. Born in Basra at the

beginning of the ninth century, flourished in Bagdad under al-Ma' mun and

al-Mu'tasim (8l3 to 849), persecuted during the orthodox reaction led by

al-Mutawakkil (841 to 861); died c. 873. "The philosopher of the Arabs;"

so-called probably because he was the first and only great philosopher

of the Arab race. His knowledge of Greek science and philosophy was considerable.

Islamic Mathematics and Astronomy A very large amount of mathematical and astronomical work was done during third period. chiefly by Muslims. It is practically impossible to separate mathematics from astronomy, for almost every mathematician was an astronomer or an astrologer, or both. Some of the most important steps forward were made in the field of trigonometry in the course of computing astronomical tables. Thus it is better to consider mathematicians and astronomers at one and the same time, but they are so numerous that G.Sarton have divided them into five groups, as follows: the geometers, the arithmeticians and algebraists, the translators of the "Almagest," the astronomers and trigonometricians, the astrologers. It is hardly necessary to say that these groups are not exclusive, but overlap in various ways. Geometers Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf was the first translator of Euclid's "Elements 'into Arabic . Al-'Abbas wrote commentaries upon them . Abu Sa'id al-Darir wrote a treatise on geometrical problems. Two of the Banu Musa, Muhammad and Hasan, were especially interested in geometry; the third, Ahmad, was a student of mechanics. Books on the measurement of the sphere, the trisection of the angle, and the determination of two mean proportionals between two given quantities are ascribed to them. They discovered kinematical methods of trisecting angles and of drawing ellipses. Arithmeticians and Algebraists The Jewish astrologer Sahl ibn Bishr wrote a treatise on algebra. The greatest mathematician of the time, and, if one takes all circumstances into account, one of the greatest of the times was al-Khwarazmi. He combined the results obtained by the Greeks and the Hindus and thus transmitted a body of arithmetical and algebraic knowledge which exerted a deep influence upon mediaeval mathematics. His works were perhaps the main channel through which the Hindu numerals became known in the west. The philosopher al-Kind1 wrote various mathematical treatises, including four books on the use of Hindu numerals. This may have been another source of Western knowledge on the subject. In any ease, the Arabic transmission eclipsed the Hindu origin, and these numerals were finally known in the West as Arabic numerals. Translators of the "Almagest" The earliest translator of the "Almagest" into Arabic was the Jew Sahl al-Tabari. Another translation was made a little later (in 829), on the basis of a Syriae version, by al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf.

Astronomers and Trigonometricians Ahmad

al-Nahawandi made astronomical observations at Jundishapur and compiled

tables. The Caliph al-Ma'mun built an observatory in Baghdad and another

in the plain of Tadmor. His patronage stimulated astronomical observations

of every kind. Tables of planetary motions were compiled, the obliquity

of the ecliptic determined, and geodetic measurements carefully made. Astrologers It is safe to assume that every astronomer was also, incidentally an astrologer. There are a few popular men, throughout the Middle Ages, who were chiefly if not exclusively concerned with astrology, they contributed powerfully to its debasement, The main astrologers of this period were 'Umar ibn al-Farrukhan and his son Muhammad Abu Ma'shar (Albumasar), Sahl ibn Bishr, and Abu 'Ali al-Khaiyat.

Al-Hajjaj ihn Yusuf

Al-'Abbas ibn Sa'id

Abu Sa'id al-Darir

Al.-Khwarizmi Abu 'Abdallah Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi.

The last-mentioned name (his nisba) refers to his birthplace, Khwarizm,

modern Khiva, south of the Aral Sea. It is under that name that he was

best knoxvn, as is witnessed by the words algorism and augrim (Chaucer)

derived from it. Flourished under al-Ma'mun, caliph from 813 to 833, died

c. 850. Muslim mathematician, astronomer, geographer. One of the greatest

scientists of his race and the greatest of his time. He syneretized Greek

and Hindu knowledge. He influenced mathematical thought to a greater extent

than any other mediaeval writer. His arithmetic (lost in Arabic; Latin

translation of the twelfth century extant) made known to the Arabs and

Europeans the Hindu system of numeration. His algebra, Hisab al-jabr wal-muqabala,

is equally important. It contains analytical solutions of linear and quadratic

equations and its author may be called one of the founders of analysis

or algebra as distinct from geometry. He also gives geometrical solutions

(with figures) of quadratic equations, for ex., X2 + 1OX = 39,

an equation often repeated by later writers. The Liber ysagogarum Alchorismi

in artem astronomicam a magistro A. [Adelard of Bath ?] compositus!' deals

with arithmetic, geometry. music, and astronomy; it is possibly a summary

of al-Khwarzmi's teachings rather than an original work. His astronomical

and trigonometric tables, revised by Maslama al-Majrti (Second half of

tenth century), were translated into Latin as early as l126 by Adelard

of Bath. They were the first Muslim tables and contained not simply the

sine function but also the tangent (Maslama's interpolation). Al-Khwarizmui

probably collaborated in the degree measurements ordered by al-Ma'nun.

He improved Ptolemy's geography, both the text and the maps (Surat al-ard,

"The Face of the Earth"). Sahl Al-Tabari Also called Rabban al-Tabari, meaning the Rabbi

of Tabaristan. Flourished about the beginning of the ninth century.

Jewish astronomer and physician. The first translator of the Almagest into

Arabic. Ahmed Al-Nahawandi Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Nahawandi. Flourished at Jundishapur at the time of Yahva ibn Khalid ibn Barmak, who died in 802-3; he himself died c. 835 to 845. Muslim astronomer. He made astronomical observations at Jundishapur and compiled tables called the comprehensive (Mushtamil). H. Suter: Die Mathematiker und Astronomen der Araber (l0, 1900) Habash Al-Hasib Ahmad ibn 'Abdallah al-Marwazi (i. e., from

Merv) Habash al-Hasib (the calculator). Flourished in Baghdad; died

a centenarian between 864 and 874. Astronomer under al-Ma'mun and

al-Mu'tasim. (He observed from 825 to 835) He compiled three astronomical

tables: the first were still in the Hindu manner; the second, called the

'tested" tables, were the most important; they are likely identical with

the "Ma'munic" or "Arabic" tables and may be a collective work of al-Ma'mun's

astronomers; the third, called tables of the Shah, were smaller. Apropos

of the solar eclipse of 829, Habash gives us the first instance

of a determination of time by an altitude (in this case, of the sun); a

method which was generally adopted by Muslim astronomers.

He seems to have introduced the notion of "shadow," umbra (versa),

equivalent to our tangent, and he compiled a table of such shadow which

seems to be the earliest of its kind.

Islamic Alchemy, Physics, and Technology The astronomer Sanad ibn 'Ali is said to have made investigations on specific gravity. Al-Kindi wrote a treatise on geometrical and physiological optics; he criticized alchemy. His writings on music are the earliest of their kind extant in Arabic; they contain a notation for the determination of pitch. Among the works ascribed to the Banu Musa, is one on the balance.

Islamic Geography, and Geology Al-Ma'mun ordered geodetic measurements, to

determine the size of the earth, and the drawing of a large map of the

world. The mathematician al-Khwarizmi wrote a geographical treatise, entitled

the Face of the Earth, which was essentially revised edition of Ptolemy's

geography; it included maps. Sulaiman the

Merchant traveled to the coast-lands of the Indian Ocean and to China;

an account of his journeys was published in 851.

Arabic Medicine There is nothing to report in this time

on either Latin or Chinese medicine, and that my account of Byzantine medicine

is restricted to a reference to Leon of Thessalonica. Practically all the

medical work of this period was due either to Japanese or to Arabic-speaking

physicians. To consider the latter first, I said advisedly "Arabic speaking"

and not "Muslim," because out of the eight physicians whom G. Sarton

mentioned as the most important, six were Christians, most probably Nistorians.

Of the two remaining, one was a true Arab, the other a Persian. A great

part of the activity of these men was devoted to translating Greek medical

texts, especially those of Hippocrates and Galen, into Syriac and into

Arabic. All of these translators were Christians, the most prominent being

Ya'hya ibn Batriq, Ibn Sahda, Salmawaih

ibn Bunan, Ibn Masawaih, and Ayyub al-Ruhawi. Ibn Sahda Flourished at al-Karkh (a suburb of Baghdad),

probably about the beginning of the ninth century. Translator of medical

works from Greek into Syriac and Arabic. According to the Fihrist he translated

some works of Hippocrates into Arabic. According to Hunain ibn Ishaq, he

translated the "De sectis" and the "De pulsibus ad tirones" of Galen into

Syriac. Jabril Ibn Bakhtyshu Grandson of Jirjis ibn JibriI, q. v., second

half of eighth century; physician to Ja'far the Barmakide, then in 805-6

to Harun al-Rashid and later to al-Ma'mun; died in 828-29; buried in the

monastery of St. Sergios in Madain (Ctesiphon). Christian (Nestorian) physician,

who wrote various medical works and exerted much influence upon the progress

of science in Baghdad. He was the most prominent member of the famous Bakhtyashu'

family. He took pains to obtain Greek medical manuscripts and patronized

the translators. Salmawaih Ibn Buan Christian (Nestorian) physician, who flourished

under al-Ma'mun and al-Mu'tasim and became physician in ordinary to the

latter. He died at the end of 839 or the beginning of 840. He helped

Hunain to translate Galen's Methodus medendi and later he patronized Hunain's

activity. He and Ibn Masawaih were scientific rivals. Salmanwaih realized

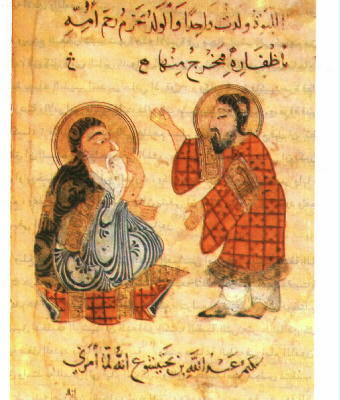

the perniciousness of aphrodisiacs. Ibn Masawaih Latin name: Mesue, or, more specifically, Mesue Major; Mesue the Elder. Abu Zakariya Yuhanna ibn Masawaih (or Msuya). Son of a pharmacist in Jundishapur; came to Baghdad and studied under Jibrll ibn Bakhtyashu'; died in Samarra in 857. Christian physician writing in Syriac and Arabic. Teacher of Hunain ibn Ishaq. His own medical writings were in Arabic, but he translated various Greek medical works into Syriac. Apes were supplied to him for dissection by the caliph al-Mu'tasim c. 836. Many anatomical and medical writings are credited to him, notably the "Disorder of the Eye" ("Daghal al-ain"), which is the earliest Systematic treatise on ophthalmology extant in Arabic and the Aphorisms, the Latin translation of which was very popular in the Middle Ages. Text and Translation Aphorismi Johannis Damnseeni

(Bologna, 1489. Translation of the al-nawadir al-tibbiya). Many other editions.

In the early editions of this and other works, Joannes [Janus] Damascenu

is named as the author.

|